The Darwinian Paradigm

The Darwinian Paradigm is, for me, ‘normal science’ (as described by Kuhn).

Anything that is normal, for me resides in a Darwinian Paradigm. In short, I write about ‘normal’ stuff.

This is my blog on science education, science and random things.

It is my ‘normal’. It may link to some of my professional work on education (teacher education) and my writing on education, science or evolution vs creationism.

I’m not the best blogger on the block, but I hope you like some of what I write.

avoiding the laundry list literature review

For anyone doing, drafting or redrafting a literature review, this is an excellent post that will help claify what a literature review is supposed to do.

I’ve been asked to say more about the laundry list literature review.The laundry list is often called ‘He said, she said” – as one of the most usual forms of the laundry list is when most sentences start with a name. And the laundry list is a problem. It’s hard to read and not very fit for purpose.

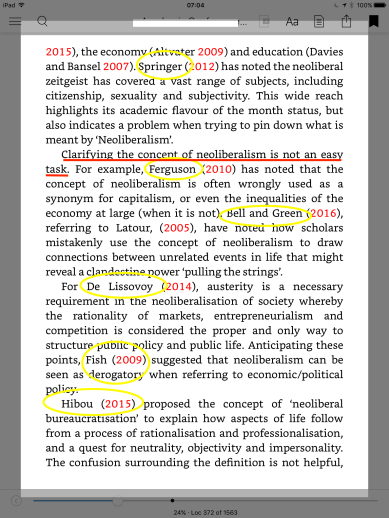

So, what does a laundry list look like? Below is a page of a published book. It is taken from a chapter reviewing the literatures on neoliberalism in ‘the university’. It’s a laundry list. I have:

- underlined in red the sentence where the author says what they are trying to do (you might call this a topic sentence)

- circled the sentences that feature a scholar as the subject of the sentence.

Now let’s see what’s going on in the writing. The second paragraph on the first page begins with the author’s intention…

View original post 1,151 more words

A brief twitter conversation on grammar schools, with Peter Hitchens

Peter Hitchens is a very successful columnist – opinion writer and of that there is no doubt. Largely I disagree with him on major issues, but that does not mean I don’t recognise his skill, his passion and his ability to put forward his view.

On the issue of grammar schools he is adamant that their demise is like removing a bridge’s keystone, the whole thing (our education system) collapses.

He is happy that Theresa May is planning to bring back grammar schools.

I am not.

In a recent, brief ,twitter conversation we exchanged views. It began with a direct tweet from me.

.@ClarkeMicah Let’s go along with grammar schools, hypothetically. That’s 1.6 million children sorted – what schools do the other 7m attend?

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

His reply?

Schools that are certainly no worse than the dud comps which most people are allocated to now. https://t.co/04RDqVxz8N

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

His reply was, in my view, rather off-hand and denied the undeniable, that comps as a whole are not ‘duds’.

@ClarkeMicah So you would write off 7 million children just like that? Despite the overwhelming evidence against grammar schools? Astonishing.

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

It seemed to me that he was unaware of any of the evidence (and there is rather a lot) that disputes the value of grammar schools as either good vehicles for improving social mobility or as better schools for the most able (the hypothesis being that the most able children would not achieve their ‘best’ in a comprehensive non-selective environment). I asked Mr Hitchens another ‘direct’ question:

@ClarkeMicah How many ‘dud comps’ have you ever visited, spent time in and gained an understanding of?

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

To be fair, from what I can ascertain from his wikipedia entry (and I know such entries can be rife with inaccuracies) he certainly didn’t attend a comprehensive in the 1960s, but there again, neither did he attend a grammar school. His academic pedigree is that of an independent (private) education and then a degree via Alcuin College at the University of York.

From ‘Dislike’ to ‘Hatred’ in one Tweet

Suddenly, I then become a ‘hater’ according to Mr Hitchens,

Grammar-haters pretend to care about losers in hypothetical grammar system.But don’t care about actual losers from selection by wealth now. https://t.co/04RDqVxz8N

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

To be fair I did state that I had attended a grammar, didn’t think it provided a good education, that my father had done so as well – not progressed to a university, but became a shopkeeper. My ‘better education’ I maintain, came via the comprehensive school I attended for most (6 out of 7) years of my secondary schooling. Of course there then came the inevitable tweets from a range of others about ‘personal anecdotes’ not being evidence etc. which, if any of them had bothered to follow the conversation I admitted in the very next tweet.

@ClarkeMicah Anecdotes (like yours and mine) aren’t evidence. Yet you deny the evidence for ideology. On that basis you’d deny gravity and evolution!

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

I do not hide the fact that I did not like my grammar school, but I do know how to check bias by looking very carefully for evidence that is independent and which may confirm or deny my position. As a scientist by initial degree, I see evidence over opinion as the standard for debate in cases such as this.

@ClarkeMicah Why do you think an evidenced based should be characterised as someone being a ‘grammar-hater’ I don’t ‘hate’ them, they are just no better

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

There was a missing word in that tweet it should be ‘evidenced based opinion’. Mr Hitchens cites ‘1000 people’ he has met with anti-grammar views being just like me.

Because I have met about 1000 people like you, before. Grammars are (or were) immensely better. Only an ideologue could claim differently. https://t.co/qjEdFJLZnj

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

OK, firstly, this is not ‘evidence’ but anecdote. Secondly, who’s the ideologue here?

Evidence Matters – It Really Does

And now we get to the really interesting part of this conversation.

Mr Hitchens asserts (with no evidence) that grammar schools are better and if you don’t see that you are an ideologue. He didn’t even attend a grammar, but ‘knows’ they are better. The best form of defence, of course, is attack and so the following tweet from him ‘demands’ evidence for my position, though seemingly no evidence is necessary for his position.

@edujdw You haven’t produced any evidence, that I have seen. But you *have* confessed to a personal prejudice.

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

The fact that I confessed to a ‘personal prejudice’ is the killer of course, designed to undermine my whole argument. I offered to send him the evidence via email if he provided a DM with an e-mail. I can understand that such a ‘famous’ person may not wish to divulge their e-mail to a mere lowly academic like me so that was not forthcoming.

OK tweets it is then.

The Evidence Against and For Grammar Schools

My first tweet was this – note, as a ‘starting point’, by no means all the evidence and not even a peer reviewed publication.

@ClarkeMicah This is a good starting point. https://t.co/nX87at21Ti and yes I have a personal dislike, supported by evidence, your evidence*for* being?

— James Williams (@edujdw) April 17, 2017

Mr Hitchens swiftly (he must be a fantastic speed reader) as, within 3 mins, he dismisses this as-

It’s the usual useless diversion into operation of tiny remaining rump of besieged grammars, no guide to operation of national system. https://t.co/ipx4AYcKBw

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

In response to my request for evidence ‘for’ grammar schools his response was simply this:

@edujdw Principally the observable collapse of rigorous exams and education in England following the abolition of most grammars 1965-75

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) April 17, 2017

This is not evidence, but his opinion (and that of many others I agree).

But hold up, what, if he and others are correct? What if the exam system had ‘collapsed’?

Even if the exam system is poor, what has that to do with the teaching in grammar schools? Grammar schools do not set the exams and the quality of the exam system is NOT the quality of the school system, it is ‘one’ measure of the quality of the system (and perhaps not the best measure).

If the exams were that poor surely schools could get 100% A* passes in no time at all leaving plenty of time for the important things like a ‘real’ education, independent of the exams.

Even if every school was a grammar school we could still have a bad examination system. To be fair he later backed this tweet with an article written in 2004, again not what I would call evidence but I do agree that the examination system was (and still is) not fit for purpose.

So what evidence did I provide against grammar schools?

I provided links to all the following:

Crook, D, Power, S, and Whitty, G. (1999) The Grammar School Question

A review of research on comprehensive and selective education London: Institute of Education

My conclusion – when you are called out to provide evidence, do so. But don’t expect the same level of detail or rigour back from a journalist or an opinion writer – their opinion, it seems, is their evidence.

My advice on evidence to journalists?

1. Your opinion, no matter how deeply held, is not evidence

2. Another newspaper article is not evidence

3. If you ask for evidence and get it be gracious, say thank you and read it, don’t ignore it or dismiss it within 3 mins.

A Christmas present from a tweeter

You make a casual remark on twitter and before long demands are made to defend a researcher’s methodological approaches.

It started innocently enough:

@Fatfonzi @RufusWilliam Boaler’s work IMO is damaging to maths education

— Tom Bennett (@tombennett71) December 20, 2016

At this point I have to state that I know Jo, know some of her work and worked with her at Sussex for a few years. That said I am not a maths ed expert, neither do I subscribe to or have expertise in her methodological approach to maths ed research. She does large scale longitudinal studies, I am more case study in history of science ed., though I also research creationism and evolution from the standpoint of the nature of science and scientific understanding.

I made a casual remark in reply – a disagreement of the opinion (remember it was Tom’s opinion) given.

@tombennett71 having worked with Jo I have to disagree. Mostly good stuff. Though don’t agree 100% (as with anyone) @Fatfonzi @RufusWilliam

— James Williams (@edujdw) December 20, 2016

Twitter, as we know, is imperfect in conveying subtlety in what you write. I said ‘mostly good stuff’ (that means the stuff I know about) yes, I admit it can be read that I am trying to defend nearly everything she has ever written which of course I have not even read, not being maths ed. I did add I don’t agree with 100% but that seems to have been lost in subsequent exchanges.

So let me state. I’ve read some of Jo’s work, I thought some of what I read was good stuff (note I’m not saying true, universally applicable, incontrovertible, God’s (if you have one) gift to maths education or a ‘paradigm shift’ in maths teaching and learning). I’m also not saying her epistemological, ontological and axiological positions are 100% and not to be disagreed with. It was a ‘casual’ comment where on reflection I should have said ‘some’ not ‘most’ – my bad!

I then had the temerity to say this which starts a mini twitter storm (actually more a brief gust in an alley)

@RufusWilliam I’m not maths, so defer to expertise, but I do rate her research/methods and have adapted for sci @tombennett71 @Fatfonzi

— James Williams (@edujdw) December 20, 2016

So right from the start I say I’m not maths and I defer to maths experts

I do rate her research in that some bits that I found interesting also worked in a science classroom but not in a way that could be reported in a peer reviewed journal. I do rate her methods – longitudinal studies using hundreds of students (though again I have not studied in depth her methodology for every study she has undertaken) but in general longitudinal studies are good – aren’t they?

Queue entrance of Twitter’s very own @oldandrewuk asking how I adapted her work in science ed.

So I said what I did

@oldandrewuk one ex is group context explanations of concepts. Works well in classes with traineees @RufusWilliam @tombennett71 @Fatfonzi

— James Williams (@edujdw) December 20, 2016

OK he thought initially I was ‘defending her research methods’ but as I clearly stated I was not, I was talking about a teaching method I found interesting and that I did a small bit of action research with a few science trainees about 6 years ago.

I also posted this, knowing the vile attempts that have been made to attack her personally, professionally and how spiteful and vile some ‘experts’ in US maths have been towards her.

@oldandrewuk btw I won’t engage with the hate filled spiteful criticism levelled by US maths people @RufusWilliam @tombennett71 @Fatfonzi

— James Williams (@edujdw) December 20, 2016

This prompts OA to write:

@edujdw @RufusWilliam @tombennett71 @Fatfonzi Oh right. So you will only listen to people who agree with her?

— Andrew Old (@oldandrewuk) December 21, 2016

Which is NOT what I said, though it’s useful to characterise me as doing this and so cast me as unwilling to acknowledge that there are any proper dissenters to her views on teaching and learning maths, nice one OA good set up.

But no, it won’t wash.

I am happy for there to be debate on the pros and cons of any educational activities, but the attacks MUST be about the issues and not the person, when it strays to the personal and attempts top get people sacked because you don’t like their views, or charges of intellectual dishonesty which were investigated in full, then dismissed, but continue to be made knowing they’ve been fully investigated and dismissed that crosses a line. I refer to the unprofessional hounding of a professional by two other maths experts who happen to disagree with Jo and what she does.

I won’t bore you with the full exchange, but it resulted in demands for me to defend her methods and research or admit I have failed to do so. I defended one aspect of the work she conducted by reproducing it in small scale. It was group work in explaining a difficult concept in a mixed ability setting. I know enough about research to know that what I did was not robust enough for me to publish myself, so I did not. I also said that the approach was interesting (which it was).

The full exchange reminded me very much of the sorts of exchanges that I frequently have with creationists on twitter – the creationist evangelicals. I don’t know OA personally, have never met him, have no idea what he is like at teaching maths. It strikes me that his approach to debating on twitter (though I could be way off the mark) is somewhat akin to an evangelical creationist in maths education terms. That is there is a right and fully evidenced and scientifically robust way of teaching and everything else is wrong. Try to even suggest that something like mixed ability teaching in maths or group work could work or be a valid way of teaching and I will challenge you to the death to prove it beyond doubt in peer reviewed scientifically valid and robust terms that can have no doubt or any flaw in its approach or else you MUST admit defeat and admit that I am right and you are wrong. What happened in the end is also what happens with many evangelical creationists – they block when you try to have a reasonable conversation and put the view that perhaps we don’t know everything, and that things could happen but it doesn’t mean you have to abandon your faith to see that other things could happen.

One further example of ‘extremis’ in OAs arguments is seen in this tweet and his response to my tweet to another tweter about science being about finding the ‘truth’. I said that only maths can claim to find the ‘truth’ science can never do this. His response to this conversation with the other tweeter was:

@edujdw @FarrowMr @RufusWilliam @tombennett71 @Fatfonzi So science is lies?

— Andrew Old (@oldandrewuk) December 21, 2016

He either does not understand science and the methods of science or is deliberately trying to get me to say that science is really lies so the can come back and prove me wrong.

Science is about the ‘best explanation’ we have for anything. At no point can we claim that explanation to be ‘the truth’ as new evidence can always contradict our best explanation – at which point we must modify the explanation or abandon it completely for a new one. So no, science does not tell ‘lies’ but neither can we claim ‘truth’ for science. Our best explanations are the theories in science.

I don’t know why OA plays these games as it always ends (with me) with him going off in a huff and blocking. He did it before then inexplicably unblocked me. I don’t know why he bothers at all with me, he clearly will not bother to engage in a proper conversation, but always makes demands and tries to ‘win’ all his arguments at all costs.

So thank you OA for the xmas present of not having to respond to your demands (not that I was going to anyway – it was not necessary and it’s not my field of expertise). It’s a pity you despise Jo and her work. She is a wonderful person, warm dedicated and always thinking of how to improve maths education for all children. No she doesn’t always get everything right, none of us, including you OA can ever do that, but at least she tries and at least she is not a vile, nasty, unprofessional maths expert, unlike her US tormentors.

Whose Knowledge is best?

By Frits Ahlefeldt (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Recently, Nick Gibb MP gave a speech in which he advocated a ‘rigorous knowledge -based curriculum’

Speaking at the launch of Parents & Teachers for Excellence last night; campaigning for a rigorous knowledge-based curriculum @PTE_Campaign pic.twitter.com/vaiR3m52JF

— Nick Gibb (@NickGibbMP) December 1, 2016

Gibb was addressing the launch of a new organisation, Parents and Teachers for Excellence (PATE).

There’s a narrative, mostly found on Twitter, but also evident in other social media and education commentary in the press, that teachers somehow eschew teaching ‘knowledge’. That knowledge is almost incidental to ‘better’ ways of teaching like group work, problem solving etc. On top of this, teacher training, we are told by others, teach theory like ‘Bloom’s taxonomy’ which is also ‘anti’ knowledge.

Such attacks are convenient sticks with which to beat the ‘progressives’ who, themselves, it is claimed, are anti-knowledge. To be honest, I’m getting quite tired of this obviously flawed logic and rhetoric.

Teachers are teaching ‘knowledge’ all the time – regardless of the methods they use. Even in group work knowledge is being delivered. I’ve yet to see any curriculum document that does not contain some form of knowledge. I’ve yet to see a lesson where a child has never engaged with any knowledge at all.

To imply that teachers – any teacher – does not deliver knowledge in teaching is frankly silly.

So what is the argument really about?

The argument is about ‘what’ knowledge is delivered and to whom it is delivered. Even Nick Gibb had to imply that there was something special about what he called for. It wasn’t just a knowledge based curriculum, oh no, this is a Conservative rigorous knowledge based curriculum and so the absurdity continues. Now, it’s not just knowledge that has to be taught, but rigorous knowledge.

What is the difference between knowledge and rigorous knowledge?

By NBC Television (ebay item front back) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Is my knowledge of Star Trek rigorous? Does the fact that I know Captain James T. Kirk’s middle name is Tiberius, after his grandfather who admired the Roman Emperor Tiberius, make my knowledge of Star Trek rigorous, or would people say that no knowledge of Star Trek is worthy or rigorous, as it is just a TV/film science fiction franchise and so unimportant in knowledge terms?

Knowing or not knowing facts about Star Trek is for the most part irrelevant. Though the science of Star Trek is worthy of note as they employ real astrophysicists while writing their scripts and bring real scientists into their narratives.

For example, is Star Trek frivolous when they go to the trouble of name checking Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer of the theory of evolution with Charles Darwin, correctly describing his view of the likelihood and probability of alien life existing in the Universe?

What it all boils down to is a value judgement and the power of a ruling elite to control what is taught (and therefore, by definition, what should be learned) by our children.

Gove was a control freak on this aspect of education – he wanted to define what history was taught and how, and strip our curriculum of American literature in favour of more British literature.

What we teach our children is not what is always useful or important.

By W.J. Morgan & Co. Lith. of Cleveland, Ohio. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Somebody, somewhere, decides that teaching Shakespeare, Dickens etc. is a necessary part of a good English education. As a scientist I ask why do we not study Newton’s Principia or Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle instead of Shakespeare and Dickens? We can learn as much, if not more, from these two classic science texts as we can from the literary classics.

The answer is that someone somewhere, who probably didn’t study the history of science, deemed them unimportant, perhaps too difficult, or boring – whatever, they didn’t make the cut into any ‘rigorous knowledge’ curriculum. Shakespeare and Dickens did.

Poetry corner

Byron, By Richard Westall (died 1836) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

I also saw a tweet that recommended children should learn poems off by heart as this was good for them.

Why is this good for them?

I am now going to show my abject ignorance. I don’t know a single poem by heart. I have fragments of lines of poems. I can do a few bits of random Shakespeare – but not because I learned it in school for English literature, but because I acted in Shakespeare as a youth.

I also fail miserably to identify songs correctly and music from the era of my youth – the 70s and 80s – some may say this is a good thing. But I’m pretty good on show tunes from musicals.

This is what puzzles me. Why is being able to identify Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto in B flat minor opus No. 23 a sign of a good education?

Correctly naming “La Cage aux Folles” as the musical which contains the song ‘I am what I am’ or knowing that ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ started life, not as a football song, but in the musical Carousel is not, it seems, the sign of a ‘good education’. Why?

Why is knowing key quotations come from the Bible or Hamlet a sign of a good education and perhaps rigour, yet being unable to correctly identify the man who gave us one of the most important phrases in science, the ‘survival of the fittest’ unimportant? By the way, it wasn’t Charles Darwin though many people think it is. The phrase finds its way into everything, from t-shirt slogans to the clarion call to arms of those who take part in TV shows like Gladiator and Ninja warrior.

Whose curriculum is it anyway?

Gather 100 teachers and ask them to construct a whole-school curriculum and what they insist ‘must be taught’ will result in a set of knowledge requirements that cannot be met.

We first did this in the 1980s with the National Curriculum (NC). Look at the various drafts and track its evolution from its inception through the various iterations and you will see the problem revealed. There is just too much knowledge for us to teach.

In the 16th Century, a Natural Philosopher (scientist) would have a good grasp of the entirety of scientific knowledge of the day. By the 19th Century, the exponential growth in our knowledge (which carries on to this day) didn’t just outstrip the mental capacity of the natural philosophers (by this time now being separated into the various disciplines we see today) but it began to overwhelm all major disciplines.

During the twentieth Century – starting from a baseline of a relatively stable unchanging corpus of knowledge within the different disciplines – we encountered issues over diversity of knowledge in the various examination syllabuses.

Surprisingly, it took until 1976 and Jim Callaghan’s Ruskin College speech to initiate the ‘great debate’ over what we should teach. This was the conception, though the gestation and birth took another 12 years, of the NC. The idea that we should have a core set of subjects with specified content that all children should be taught.

It was Kenneth Baker who acted as the midwife and brought into the education world ‘The National Curriculum’. Baker’s baby, however, went much further than his boss,the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, wanted. She envisaged a small core curriculum of maths, English, Science. Baker was much more ambitious and wanted every subject covered. He got his way when he threatened to resign as Secretary of State for Education unless the NC was implemented in full. Such a resignation, so close to the launch of this major curriculum reform, some say the most important education initiative since the 1944 Education act, would have seriously embarrassed the government, Thatcher’s government.

Since that day the curriculum has undergone numerous reforms and, in my own subject area, science, has been both concentrated, diluted and re-ordered to such an extent that, to use an evolutionary analogy it could be deemed to be ‘not fit for purpose’ and doomed to become extinct. The difference between the initial document and the present day ‘animal’ is much like the relationship between the early mammals and current Homo sapiens. I can see commonalities and links, but the fundamental differences make us very different species.

I have no objection to the teaching of ‘knowledge’. Even in Bloom’s Cognitive domain, if you think about what it is actually saying, rather than what you might think it is saying, things like synthesis, evaluation, application (higher up the domain) cannot be achieved without the foundation of knowledge. Yes, knowledge is ‘at the bottom’ because it recognizes that without knowledge there is nothing to synthesize, or apply, or even evaluate. When it comes to those, oh so despised (by evangelical traditionalists), activities like group work, problem solving etc. none of that can happen without knowledge.

Knowledge is vital in any teaching and learning. The debate is not about whether we have a ‘knowledge based curriculum (even a rigorous one) or not’ knowledge in teaching should be a given foundation.

The debate must be on what knowledge we teach, whose knowledge deserves to be foremost in our various subjects and why that knowledge, above all the other knowledge that could be included, should be prized.

Why urban myths about education are so persistent – and how to tackle them

![]()

James Williams, University of Sussex

As children across England and Wales go back to school, it’s worrying to think that in many classrooms, teachers will be starting the new term believing in teaching “methods” that have been debunked by research evidence.

One of the most persistent “edumyths” is learning styles – the idea that there are a number of styles of learning, such as visual, aural or kinaesthetic – and that certain children respond better if teaching is directed towards their preferred learning style.

Learning styles have been far too easily accepted by some schools and teachers despite the lack of evidence of their effectiveness. The prevalence of references to learning styles in School Centred Initial Teacher Training (SCITT) programmes from Durham, to Surrey and Cornwall shows how ingrained the concept still is. Despite learning styles being debunked, the concept still forms part of the formal school-based training of a number of teachers across a number of subjects.

So why, in the face of such damming evidence, are edumyths still accepted and used by schools and teachers?

Cat out of the bag

A simple Google search for “learning styles” reveals 5.9m links. Many websites are devoted to it alongside other related educational “approaches” and variations on the theme. Sites provide “testimonials” of effectiveness, but very few provide any solid peer reviewed evidence to back this up.

Studies from the fields of psychology and medical education have shown the futility of learning styles as an effective teaching approach. A systematic and critical review of learning styles catalogued 71 different learning styles models, 13 of which were identified as “major models”. Suffice it to say that, as education scholars Myron Dembo and Keith Howard concluded in a 2007 paper on the use of learning styles in education:

Learning style instruments have not been shown to be valid and reliable, there is no benefit to matching instruction to preferred learning style, and there is no evidence that understanding one’s learning style improves learning and its related outcomes.

Spread of education learning myths

From the ubiquitous Brain Gym that flourished in schools in the late 1980s and early 90s, to the idea that some people use one side of their brain more than the other, or the “fact” that we only use 10% of our brain, exactly how these myths spread is a complex and difficult to understand process.

Monkey Business Images/www.shutterstock.com

The blame has been laid at the door of university initial teacher training courses, as well as commercial companies, individual “education consultants” and some teachers. Even the Department for Education (DfE) pedalled the view that universities promoted “useless” theories in teaching and learning.

Yet, a survey by the Wellcome Trust, reported by the charity Sense about Science showed that teachers were not getting learning styles predominantly from their university teacher training. Instead, they:

Commonly come across neuromyth-based methods by word-of-mouth – from their institutions (53%), individual colleagues (41%), and from training providers (30%), who are often linked to those promoting neuromyths.

Are myths necessary?

Myths quite often have some basis in reality. For learning styles, there’s no doubt that people will report a preference for how they learn, but this does not mean they learn better using that “style”. Learning styles also gain traction in the education community because of a general conflation with a push to deliver content in the classroom in a variety of ways. How information is presented to children needs to be varied, if only to stop boredom kicking in. The best teachers have a variety of approaches that mix and match the best learning experiences for their children.

Variety in how information is presented and ideas are explored is not a bad thing. The problem is that this can also lead inadvertently to providing evidence that the idea being used, far from being a myth, actually works. On many occasions I have had teachers tell me that learning styles work, regardless of what the research evidence says. At this point, it’s worth remembering the Hawthorne effect: simply doing something different can have an effect and that effect can be a positive one, but the effect may not be real.

Training is key

The way to tackle edumyths surely must be to provide teachers with the evidence and show them that the idea they accept as true is actually a myth. If only it were that simple. The social psychologist Norbert Schwartz and his colleagues showed that often, when presented with compelling evidence that certain statements were false, people often mis-remembered the false statement as being true.

The move to sideline or even remove universities from initial teacher education and increase school-based teacher training programmes may have the opposite effect to that hoped for by the DfE. Instead of edumyths and “useless” theories dying out, they might become more prominent and even more difficult to remove from teaching. Once misconceptions are implanted, they are very difficult to remove. If teacher education shifts further towards a school-based model of delivery, the potential for implanting misconceptions increases exponentially.

Teachers need two things to improve their practice and eliminate what doesn’t work in favour of what does. First, training in how to look beyond the attractive yet empty claims of the peddlers of educational snake oil and second, time to undertake effective professional on-the-job training that has been shown to be both reliable, rigorous and effective.

James Williams, Lecturer in Science Education, Sussex School of Education and Social Work, University of Sussex

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

What’s happened to democracy in our education system?

Democracy is a strange thing. The basic idea – that people have a right to decide is fine in principle, but what if the ‘people’ make the wrong choice? Who decides what’s right or wrong? I voted to remain in the EU referendum. 17 million people disagreed with me only 15 million agreed.

I still believe the choice was wrong, but try telling that to a gloating brexiter. “Who cares what you think”, I’ve been told, “we won so shut up and accept it”. I can argue that there were lies and deceit (actually on both sides) or that the question was too simplistic given the complexity of our relationship. I can even point to the drop in the value of the pound – which, by the way, increased the cost of my short summer break by hundreds of pounds. All I get back is “WHO CARES, WE WON!” Democracy has been reduced to a win/lose game.

You choose your side and hope it’s the winning side.

Education is not a game

The win/lose game has been going on in education for many years. But it’s never been as intense as in the last six years. A politician, by the name of Gove (remember him?), wanted to ‘win’ at all costs. He had enemies that he needed to defeat. His enemies were the enemies of his predecessors who challenged, but never fully won their battles with them. The teaching unions, the local authorities, the university education departments were all ‘bad guys’; ‘the Blob’; ‘enemies of promise’; ‘Trots’, that needed eradicating. Kill these groups and education would be back to where it should be – selective, ordered, pumping children full of facts and full of the traditional academic subjects and none of this trendy, irresponsible child-centred learning.

If it works for them, it’s bound to work for us

Gove’s bullying, autocratic narrative, right from the moment he took office, was breath-taking. He cherry picked successes from all over the world and simplistically and wrongly decided that a simple transplant of ideas would ‘fix’ a system he saw as broken beyond redemption. Only wholesale change would do.

Shanghai maths was lauded as the only reason students in the far east succeed where our students fail. Gove, then Morgan, now Gibb completely ignore the social and cultural context and the conditions under which teachers work in China. The narrative persists today – Shanghai maths is still being touted as ‘the answer’, and still the social context and the working conditions of the teachers is ignored.

Expert panels were hired for a curriculum review and summarily dismissed if they came up with the ‘wrong’ answer – that is, something Gove didn’t like. His tenure became so bad he was considered toxic and a threat to the success of the Conservative party in the 2015 election. He was summarily dismissed. Since then, his fall from grace has been quite spectacular.

The ‘Big Idea’ – every school better than the average

Gove’s ‘big idea’ was the academies programme. Here’s where democracy (not to mention knowledge of averages) really left the building, seemingly never to return. In ‘consultation’ after ‘consultation’, in vote after vote, plans to convert schools were rejected. The DfE response was, to be fair, consistent. ‘The only way to improve any school is to turn it into an academy’. Gove removed governing bodies that objected and put in place puppet governors who would do his bidding. The outcomes of any, seemingly all, consultations were systematically ignored. At the same time, parents were being told how important ‘parental choice was’ how parents should be able to choose where to send their offspring.

This paradox of simultaneously promising a democratic education system where parents have freedom of choice, whilst denying, in an overtly autocratic way, any dissent over the government ‘choice’ of who and how schools should be run did not seem to trouble the political elite at all.

It’s fine to ignore the will of the people, except…

The current government could ignore the outcome of the referendum; it was a close run thing, 52% for exiting the EU – 48% for staying. But, quite rightly the majority would say, that’s undemocratic. However, ignoring a parental vote where over 90% were against conversion to academy status, e.g. at Downhills Primary, was considered acceptable to the DFE.

There have been many controversial academy conversions, Downhills Primary school being an early, acrimonious and bitter fight against academisation which was lost. Others have been able to resist conversion, such as Hove Park school in Brighton. But the key thing in all these fights and in the programme of academisation which still rolls on unabated today is the loss of local accountability and the defeat of democracy.

Pedantic semantics

I know that a consultation and a referendum are two completely different things, but they are both tools of democracy – a way for the people to be heard, listened to and changes made in accordance with those views. But, as I was reminded once by a member of the DfE Press Office, ‘a consultation is not a negotiation. We are under no obligation to change our plans or abide by the results of a consultation. It’s merely something we have to do, consult’. Well the answer to the embarrassment of ignoring consultations is of course to change the law and remove the need to consult at all – which the DfE now plans.

Autocratic Failures

Recently we were told about the Lilac Sky Schools Trust which, having failed to improve schools under its control, has just ‘handed back’ to the DfE control of nine academies across Kent and Sussex. Here we also see another complete failure of democracy. These schools will be brokered to new Multi Academy Trusts – most likely at a considerable cost to the taxpayer – with no consideration of what parents or teachers would like to see happen.

The academies programme has systematically failed to live up to its expectations as the sole tool of school improvement. This fact has never been admitted or entertained by Gove or Morgan. Whether Justine Greening succumbs to the will of her party, and is still intent on destroying the State Education system via the academies programme (most likely with the goal of full privatisation) remains to be seen, but surely failure after failure must raise serious questions about the academies programme? Perhaps she could be honest with the electorate just once and admit that academisation is not a magic bullet, but a vast vat of snake oil sold by a charlatan salesman with no experience or qualifications.

- By Clark Stanley (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Where lives matter, democracy is essential

The future of our education system is not a win/lose game to be played by politicians settling old political scores against their perceived ‘enemies’. With matters such as the future education of our children at stake, an autocratic approach that ignores the key stakeholders cannot be seen, even remotely, to be democratic. It is quite simply a dictatorship. By all means where matters are relatively inconsequential be autocratic – a democratic, consultative approach for every decision would result in no decision ever being made. But these are not inconsequential decisions, they are major decisions that will alter the educational landscape for decades, perhaps permanently.

As Mr Spock says at the end of Star Trek III: The Wrath of Khan (1982), “Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh…” Kirk finishes “…the needs of the few.” Spock continues, “Or the one.” Since 2010, the needs of the one – the Secretary of State for education – have vastly outweighed the needs of the many. It’s time democracy was restored to our education system and the needs of the many become the driving force for change.

Love and Hate – two powerful human emotions

There are two young children at the moment who will be struggling to understand the concept of hate. A hate so powerful it has taken the life of their mother. The children of Jo Cox, Labour MP for Batley and Spen, who was senselessly and brutally murdered could easily grow up to hate. I sense, from reading a statement made by Brendan Cox, their father, that he will do everything in his power to stop that happening.

In America, there are many families who are also struggling to understand why their loved ones were killed, simply because they loved someone of their own sex. Think about that, 149 people were killed, scores of others injured, not because they hated, simply because they loved.

I struggle to comprehend this.

On my way to work I pass my local primary school and since the horrific events in Orlando, they’ve flown the rainbow flag at half-mast. They shared the grief, recognised the love and did not buy into the hate.

There is much we can do as a society to stem the rise of such a destructive hate. One simple, yet important step is to think carefully about what we say and how we say things. We must exercise caution and apply a logic to our thoughts to ensure that we do not unwittingly feed the hate that dwells in some people.

Yet it seems to me that both caution and logic are missing from the campaigns of many of the high profile politicians trying to ‘win’ our vote in the upcoming EU referendum.

I was 16 when we last voted, but if I could, I would have voted to join. In this vote, I will vote to remain. My vote however hasn’t been ‘won’ by either the ‘in’ or ‘leave’ campaigns.

Both sides have twisted facts, told half-truths, spun stories trying to persuade us to vote ‘their way’. Neither side has convinced me. I’ve decided how to vote by looking beyond the hate and rhetoric.

What disturbs me most during this whole campaign is the stirring of a form of hate that I loathe. The ‘problem’ we’ve been told by both sides is ‘people’. ‘Too many people’ or ‘the wrong sort of people’ worst of all ‘foreigners coming here’. When it’s alleged that the cause of many of our ‘problems’, from housing to healthcare from school places to jobs, is defined by the existence of certain groups of people, you aren’t going to promote love, quite the opposite.

It has been, for me, a campaign characterised by hate.

Love and hate are powerful human emotions, so powerful they can unite or destroy, not just individuals, but whole countries. Jo Cox’s husband summed hate up perfectly for me, hate, he said doesn’t have a creed, race or religion, it is poisonous.

Too often, rather than attacking problems, we’ve end up attacking people. This builds resentment and that leads to hate.

The world is full of problems, but if all we do is attack people, for their beliefs or their ethnic origins, for what they have or do not have, then we poison the minds of others. They see the attacks and buy into the mistaken belief that the problem resides in the existence of ‘these people’. That’s when the hate takes hold.

Ultimately there’s just one race – the human race. We all inhabit the same planet, we all depend on each other and our ecosystem. Yes, I know that there are different cultures, religions, characteristics etc. that ‘define’ groups of people, but if you look at yourself in a strictly biological sense, you might be surprised.

I recently had my DNA analysed to look at my ancestry. I was surprised to find that I have 39% Irish, 32% British, 14% Scandinavian and 1% Iberian Peninsula heritage. I know this is not something to rely upon 100%, but it set me thinking. If we did vote to leave, am I ‘British’ enough to stay? I look, sound and behave very British (I’m told). Yet my DNA tells a different human story that I’m now motivated to investigate. Scandinavia? Really? The Irish I can see, I am Welsh, born in Wales – St Patrick, patron Saint of Ireland, was, after all, Welsh.

It’s easy for people to make assumptions about others and for those assumptions to be quite wrong. If we make too many assumptions, it’s a short jump to making illogical and incorrect conclusions. The path to hatred then is a very short one.

White Paper – No Forced Academisation: More of a U-bend than a U-Turn

I’m no plumber, nor am I a professional stunt driver, but I do know the difference between a U-turn and a U-bend.

Today Nicola Morgan announced that no longer would she be seeking to bring in legislation to force all schools to be or on the road to being an academy by 2020/22.

Predictably the twittersphere erupted with joy at this apparent U-turn. Except it is no such thing. The objective of full academisation remains. It will be achieved in other ways.

The press release making the announcement has some disturbing detail which people need to be aware of, especially as it shows this is by no means a U-turn.

Looking at the press release in more detail exposes the concession that’s really an admission that it was never going to succeed in the first place.

…the government is committed to every school becoming an academy. This system will allow us to tackle underperformance far more swiftly than in a local-authority-maintained system where many schools have been allowed to languish in failure for years.

So no change here from their direction of travel and their mistaken belief that academisation achieves improvements in schools faster than leaving them in LA hands, a claim that has been refuted time and again.

Since launching our proposals in the education white paper, the government has listened to feedback from MPs, teachers, school leaders and parents.

It is clear from those conversations that the impact academies have in transforming young people’s life chances is widely accepted and that more and more schools are keen to embrace academy status.

I don’t know about you, but either this is a sign of delusion or bad hearing. Where is the evidence to support these claims? All the feedback I’ve seen and read about is negative towards forced academisation, including many, many Conservative LAs and MPs.

The ‘listened to feedback’ is of course the important phrase. It’s Nicky Morgan’s hopeful ‘get out of jail free’ card. It’s not a U-Turn but, a listening government that cares about what the experts think and is willing to change things.

And now we come to the sting in the tail – the devil in the detail or whatever you wish to call it.

In addition, the government will bring forward legislation which will trigger conversion of all schools within a local authority in 2 specific circumstances:

- firstly, where it is clear that the local authority can no longer viably support its remaining schools because a critical mass of schools in that area has converted. Under this mechanism a local authority will also be able to request the Department for Education converts all of its remaining schools

- secondly, where the local authority consistently fails to meet a minimum performance threshold across its schools, demonstrating an inability to bring about meaningful school improvement

These measures will target those schools where the need to move to academy status is most pressing. For other high-performing schools in strong local authorities the choice of whether to convert will remain the decision of the individual schools and governing bodies in question.

And this is how they think they can achieve the full academisation without the need for legislation.

Having starved LAs of funding and making them pay for schools that wish to convert or absorb the debt of any school in deficit it forces to be an academy, it’s clear that many LAs will have a real problem. It’s likely that the leafy Conservative LAs will be far less affected by this than many other LAs struggling in areas of high deprivation etc. Cheekily they say that they will grant an LAs request for remaining schools to convert – and you can bet that they will shout out loud that they weren’t ‘forcing’ it was a ‘free (Hobson’s)’ choice.

The performance threshold will also be a smoke screen. Having seduced as many high performing schools as possible to convert – often with the lure of cash, what’s left is bound to be ‘underperforming’ so the system is gamed towards LAs ultimately losing their schools.

No doubt there will also be the spectre of forced academisation for schools that don’t meet the DfEs ‘targets’ (even though they can change a target to an aspiration on a whim and duck any requirement to meet it – I give you the National Broadband target and, today, the target for forced academisation becoming an ‘aspiration’).

Recall that GCSEs, and National Tests at KS2 have, by the DfE’s own admission become much harder, more rigorous. It’s likely that pass rates will fall. After all that’s what they wanted when they took office. Pass rates were too high, they said, artificially high as exams were dumbed down. This being the case, finding ‘failing’ schools will become much easier – especially, I suspect in the primary sector where the KS2 tests seem to me to be ridiculous for 11 year olds.

So why a U-bend and not a U-turn? It’s all about the direction of travel. In a U-Turn the direction of travel is reversed. In a U-bend the direction of travel of the water detours, but ultimately still it goes down the drain. It seems the DfE is willing to flush our education system down the drain in an effort to fulfil their education ideology – regardless of the evidence and even the protestations of their own more moderate MPs and supporters.

One thing is sure. This is a huge climb down and humiliation for the Secretary of State who only two weeks ago said there is “no reverse gear” on the government’s plan to turn all schools in England into academies by 2020 well, she found the reverse gear on the legislation bus, but the academy car is still going in the same direction, no reverse gear there it seems.

The Mysterious Case of the Disappearing Schools. Or “Of Course It’s Bloody Privatisation”

A brilliant excoriation of all those who suggest that forced academisation is not a danger to the independence of our local schools.

This week, Nicky “I’m not Michael Gove, Honest” Morgan and her chum George “I’m not Satan, Honest” Osborne, announced that every school in England would be forced to become an academy by 2022. This has proved, to put it mildly, a little controversial. Opponents of academization, both forced and unforced, have generated a petition of more than 100,000 signatures already, while unions, teachers, politicians and Mumsnet(!) have united in fairly vitriolic opposition. Even Tristram Hunt and David Blunkett came out against this, which tells a remarkable story in itself. However, the “Glob“, as Francis Gilbert termed the very vocal and influential minority who actively support Gove’s privatisation agenda, has been predictably active too. More chaff has been thrown out by supporters of this policy in the last week than the RAF chucked out of its bombers over Germany in 1944, and all with the same intent: to obscure…

View original post 3,660 more words

An obituary: farewell to your Local Education Authority

James Williams, University of Sussex

By announcing that all schools will be expected to become academies, George Osborne has foretold the death of local authority involvement in education.

Born on December 18 1902, Local Education Authorities (LEAs) will likely have their life support switched off sometime in 2022, by which time all schools will be expected to be on course to becoming academies. The local authorities will leave behind a number of precious local services, their future somewhat uncertain.

Despite their long life, LEAs have not been universally popular, making a number of enemies: the late Margaret Thatcher and former education secretary Keith Joseph, to name but two. Between them they killed off the Inner LEA, but the behemoth that was the remainder of the local education authorities remained.

The death of local education authorities then seemed inevitable after they lost many of their powers of control over schools with the 1988 Education Reform Act. For many years since, their role has largely been one of scrutiny and support, but for some this will be very badly missed.

This time, the Conservatives intend to deliver a fatal blow. But there are five ways that schools and children will lose out from the demise of local authority control of education.

1. A local champion for vulnerable children

Local authorities must currently engage with parents and schools to ensure that the right provision for every child is available locally. Ensuring the specific needs of every child are met is hugely complex and even local authorities struggle to meet their responsibilities at times.

As education is fragmented, there will be concerns over how parents will be able to negotiate the minefield that is school admissions, with each academy or trust being its own admissions body.

Legally, local authorities have the responsibility to provide a school place for every child. If every school is an academy, local authorities or councils will have no power to require schools to expand their intake or take on any child. Already, LEAs are warning that finding school places for all is becoming “undeliverable”.

Currently, parents can take a local authority to a tribunal if they feel the needs of their child are not being met. It’s unclear how this will work if the local authority in effect ceases to exist.

2. A local vision for schools

With the demise of LEAs, many schools will be run by multi-academy trusts (MATs) – chains of academies run by the same sponsors. Many trusts operate a number of schools, sometimes in different local authority areas. Some may know more about the local community than others.

The only answer the Department for Education has for under-performing academies or trusts is the transfer of schools from one trust to another. This is likely to increase, alongside the incorporation of standalone academies into existing and new trusts.

The governance of academy chains has been questioned, most recently by the current head of schools inspectorate Ofsted, Michael Wilshaw, who highlighted several underperforming MATs.

Ultimately, it is likely to be the vision of the trust, not the community, that schools will adopt – and parents will have to live with it.

3. Local forum for school improvement

School improvement arises from the efforts of people, not structures. A structural change will not deliver long-term sustained improvement in itself.

Local authorities have provided a platform for a range of collaborations between heads, teachers, various schools and local and national services. Admittedly, some authorities are better at this than others, but the setting up of a free market competitive model for school governance where academy trusts actively compete rather than collaborate cannot be a good model for mutual improvement.

4. Loss of essential services to schools

Local authorities provide many services to schools, from the vetting of contracts and human resources management, to payroll services and delivering expertise in commissioning, tendering and procurement. They also provide many support services from school transport and peripatetic music teachers, to anti-bullying advice and educational psychology services.

Pens poised for new contracts.

Smiltena/www.shutterstock.com

With academies funded directly by central government, local authorities will lose much of their funding as a result of the push to academise. This may well put some of these services at risk or increase their cost. If they are large enough, some MATs may be able to replicate the cost savings of local authorities by clubbing together and contracting such services. But small rural schools who depend on services offered by the council may struggle to afford them.

5. Learning from the past

The Conservatives have learned from Labour’s failure in the 1960s to completely eradicate grammar schools. The process of ending selection was resisted by some, most notably Kent, and the law never changed to ban or force grammar schools to close – it just prevented the opening of new ones.

They also learned from their own failure in the 1980s and 90s to abolish local authorities and establish more independence for some schools under what was called the grant maintained programme. Following Labour’s landslide election victory in 1997, a new act was passed in 1998 that reversed the grant maintained status of schools.

Putting these laments for the demise of the LEA aside, the evidence that academies are the best model for school improvement is severely lacking, especially for the poorest students. Research suggests that underperforming schools actually improve much faster under local authority supervision.

What the future holds for local authorities and education is extremely uncertain. The devil will be in the detail of the government’s planned legislation.

![]()

James Williams, Lecturer in Science Education, Sussex School of Education and Social Work, University of Sussex

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.